Options are not just a tool for speculation. They are, above all, a flexible financial contract that gives the right, but not the obligation, to execute a transaction in the future. Understanding options is fundamental to professional trading and risk management in financial markets.

What Is an Option?

An option is a financial contract that gives its buyer (owner) the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a specific underlying asset (stocks, indices, commodities) at a predetermined price before or on a specific date.

For this right, the buyer pays a premium (option price) to the seller. The option seller, in turn, undertakes to fulfill the terms of the contract if the buyer decides to exercise their right.

Two Main Types of Options

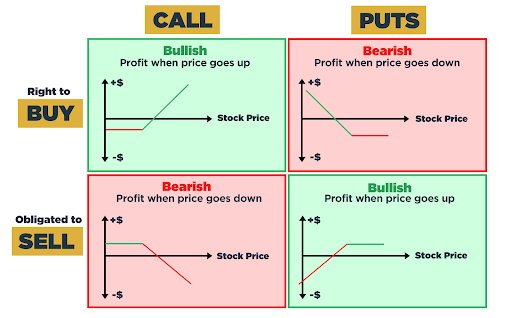

There are two fundamental types of options (Call and Put), which create four main positions:

- Buy (Long) Call Option – an option contract that gives the holder the right to buy an asset at the strike price.

- Buy (Long) Put Option – an option contract that gives the holder the right to sell an asset at the strike price.

- Sell (Short) Call Option – a short call obligates the call seller to sell an asset to the call buyer at the strike price if exercised.

- Sell Short) Put Option – a short put obligates the put seller to buy an asset from the put buyer at the strike price if exercised.

Schematically, it looks like this:

Key Contract Parameters

Each option contract has three main characteristics that determine its value and mechanics:

- Strike Price

- Expiration Date

- Option Status

What Is the Strike Price?

This is a predetermined price at which the underlying asset will be bought or sold if the option is exercised.

Example:

You bought a call option on Apple shares with a strike price of $180. This means that you have the right to buy Apple shares for $180, regardless of their actual market price at the time of expiration.

If the market price becomes $190, you will make a profit ($190 – $180 = $10).

If the market price is $170, you will not buy at $180, and the option will most likely expire worthless.

The strike price is the key level that determines whether the option will be “in-the-money (ITM)” or “out-of-the-money (OTM).”

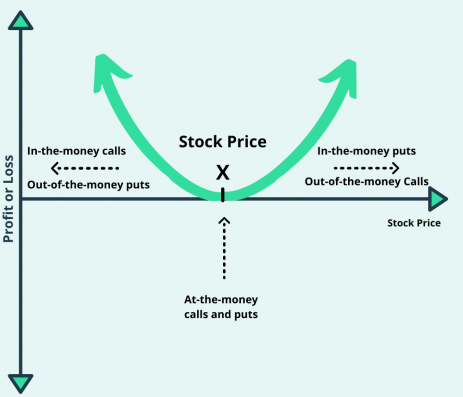

What Are ITM, OTM, and ATM?

1. In-the-Money (ITM) Option

What it means: Your option contract is profitable and has intrinsic value if you decide to exercise it immediately.

- For a call option:

- Rule: The market price of the stock is HIGHER than your strike price. You can buy it cheaper than on the market.

- In simple terms (example): You have the right to buy an iPhone for $1,000 (this is your strike price). Currently, this iPhone costs $1,200 in the store (on the market).

- Result: It is profitable for you to exercise your right to buy for $1,000 and immediately sell for $1,200. Your option is “in the money.”

- For a put option:

- Rule: The market price of the stock is LOWER than your strike price. You can sell it for more than the market price.

- In simple terms (example): You have the right to sell your old car for $5,000 (this is your strike price). But now, on the market (in the store), the same car costs only $4,000.

- Result: It is profitable for you to exercise your right and sell it for $5,000, because it costs less on the market. Your option is “in the money.”

2. Out-of-the-Money (OTM) Option

What does it mean? Your option contract is unprofitable and has no intrinsic value if you decide to exercise it immediately.

- For a call option:

- Rule: The market price of the stock is LOWER than your strike price.

- In simple terms (example): You have the right to buy an iPhone for $1,000 (your strike price). But right now, it only costs $900 in the store (on the market).

- Result: You won’t buy it for $1,000 if you can buy it cheaper ($900) directly on the market. Your option is “out of the money.”

- For a put option:

- Rule: The market price of the stock is HIGHER than your strike price.

- In simple terms (example): You have the right to sell a car for $5,000 (your strike price). But now, on the market (in the store), the same car costs $6,000.

- Result: You will not sell it for $5,000 if you can sell it for more ($6,000) directly on the market. Your option is “out of the money.”

3. At-the-Money (ATM) Option

There is a third state: when the market price of the stock is equal to your strike price. At this point, it doesn’t matter whether you execute the contract or not. This is the point of zero intrinsic value.

What Is Expiration?

Expiration is the date when an option contract ends.

In simple terms: It’s like an expiration date. After this date, the option is either automatically exercised or simply “expires” and no longer has any value. It is the last day when the option holder can exercise their right to buy or sell an asset at a predetermined price.

Why it matters: The closer the expiration date, the faster the option’s value decreases (theta decay). At this point, the final financial result for all parties to the contract is determined.

Volatility and the Fundamental “Greeks”

These are the famous “Greeks” – the sensitivities of an option’s price to various factors.

- Delta (Δ): The most critical “Greek.” It shows how much the option price will change if the underlying asset’s price changes by $1. It is essentially the probability that the option will expire “in-the-money” (ITM), and it is a measure of directional risk. How closely your position resembles owning the stock itself. Δ=0.50 means the position behaves like half a share of stock.

- Gamma (Γ): Shows how quickly Delta will change. Gamma is a measure of secondary directional risk. This is the “acceleration” of your position. High Gamma means Delta can change sharply with a small price movement, requiring active management.

- Vega (V): Shows how much the option price will change if the market’s expected volatility (Implied Volatility) changes by 1%. Vega is the measure of volatility risk. It’s the sensitivity to fear or euphoria in the market.

- Theta (Θ): Shows how much value the option loses over time (time decay). This is the “time tax.” Almost all options lose Theta daily, especially rapidly just before expiration.

- Rho (ρ): Measures sensitivity to interest rates.Rarely the main metric for short-term strategies. Important for long options and for accounting for interest rate risk.

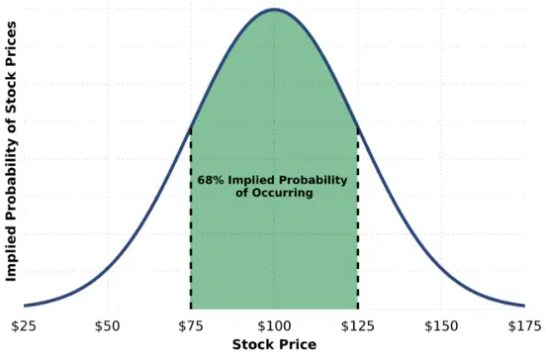

What Is Implied Volatility (IV)?

Implied volatility is the predicted (expected) volatility of the underlying asset that the market incorporates into the option price. In other words, it shows how much the market expects the price of the asset to fluctuate in the future. This is not historical volatility (which shows how the price has fluctuated in the past), but an outlook. It is measured as a percentage and is usually annualized.

In short, the higher the IV, the more expensive the option, because greater expected fluctuations mean greater risk and potential profit.

How Does Implied Volatility Change?

- IV is not constant. It changes depending on market conditions and demand for options:

- During panic or high uncertainty (e.g., financial crisis, important news, company report), IV increases because traders are willing to pay more for hedging.

- During calm periods, IV usually decreases because less volatility is expected.

The Relationship Between the Option Price and IV

What Implied Volatility Depends on?

- Market uncertainty – news, macroeconomic data, geopolitics.

- Supply and demand for options – if many traders buy options, IV rises.

- Option expiration date – short-term options are more sensitive to news, long-term options are less sensitive.

- Strike price relative to market price – often, extreme strikes (deep OTM or ITM) have higher IV.

- Historical volatility of the underlying asset – if past fluctuations were high, IV may also be high.

In future digests, we will look at popular option strategies and explain how professionals earn money on options through dynamic hedging and how they earn money regardless of where the asset price goes.